Tales of Domestic Struggles & Joys... and Taking Down Injustice

What the Middle Grade novel series The Penderwicks taught me about fighting racism and what it means to be human.

Jo: “Who will be interested in a story of domestic struggles and joys? It doesn’t have any real importance.”

Amy: “Maybe we don’t see those things as important because people don’t write about them.”

- Greta Gerwig, Script “Little Women”

I have finally met the Penderwicks. Everyone has been telling me I should read them, but I resisted because I knew I would eventually be reading them aloud to the boys and I didn’t think they were quite ready for them (they’re not). But on the urging of some trusted book recommenders (ie: my tween neighbors and my sister in the very same week) I caved in and subsequently raced through the series.

For those of you who have yet to meet the Penderwick family, they are a motherless flock of four sisters with a kindly professor father. In these middle-grade novels, the sisters have small adventures, make new friends (one being a lonesome musical boy living in the mansion next door), and experience the drama that comes from making mistakes, arguing with siblings, and being a bit too impulsive.

In other words, nothing much happens. Much like in Little Women.

Of course, there are clear literary references to Little Women throughout the series - but I think the deepest similarity is not that the author Birdsall is throwing in literary Easter eggs, but that at its heart, both books are domestic dramas. The action is not rescuing stranded heroes, or finding hidden treasure (as the third and literary-leaning Jane Penderwick would have it). The action is burning brownies, figuring out how to get over your shyness and make a friend, trying to let go of sibling jealousy, grieving a death, or sorting out what to do about your first crush. It’s the sisters, and their friendship that is the heart of the action.

So, clearly, plenty is happening — in both the Penderwicks and Little Women. But the action is internal character development. The stage is small : one family.

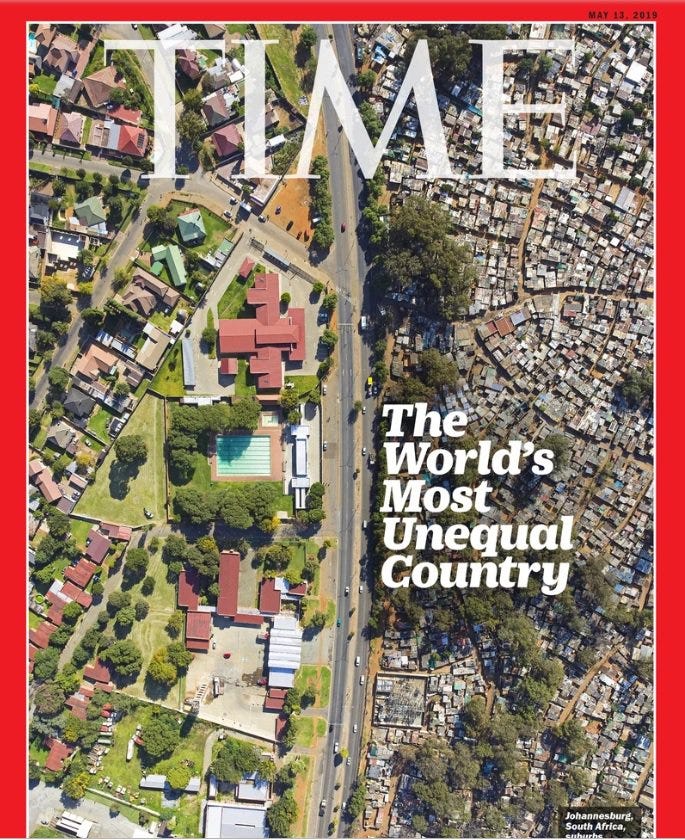

Last month I was able to spend some time with some American college students who were visiting South Africa while taking their philosophy/theology course “Contemporary Christian Belief”. The goal of the course was to think about some big questions like: “What does it mean to be made in the image of God?” and “What is a theology of beauty?” “How can a good, powerful God allow such suffering and pain?” They were considering these questions in light of how the South African church has answered these questions, both historically and today.

Let me tell you, it is profound to consider how a good, powerful God allows suffering when hearing about the horrors of apartheid and the complicity of the white South African church, or hearing about the after-effects of the HIV/AIDS pandemic. It is profound to consider the importance of having a correct theology of the Image of God while ricocheting between the townships of Khayelitsha, the Cape Flats, and the trendy restaurants of the Cape Town Waterfront.

On the trip, we discussed different views of what it means to be made in the image of God. One of the common arguments is that to be made in God’s image is to reflect his creativity, his beauty, and his intellect. It’s one you hear a lot when you hang out with writers and artists. We are culture makers. We are different than animals. We think abstractly! We create!

And yet, standing on Robben Island, the high security prison that held Nelson Mandela and other resistors to apartheid, you can quickly see the dark side of such thinking. Even on Robben Island, the rules of apartheid were enforced through uniforms and rations. “Asiatics” (South Africans of Indian descent) and “Coloreds” were given long trousers and better food. They were considered closer to the “civilized”, “intelligent” whites. “Bantus” (Black South Africans) were given shorts, like children, and the bare minimum of food. If being made in God’s image has something to do with your abilities to reason or create, all it takes is a group to consider someone “less” in those areas, and suddenly, they are less human. You can justify all sorts of atrocities when people are not seen as people. This racist thinking was embraced and propped up by many white churches, sometimes coated in paternalistic language that sounded benevolent, but was an excuse to claim superiority and power. Their theology found a way to exclude black people as being made in the image of God. Even the amount of jam they doled out became part of their twisted logic to keep power and dehumanize others.

Clearly, the Image of God has to mean more than just our human capacities for abstract thought or creativity if it is going to include all people (old, young, disabled, unborn, sick, the list goes on), and protect against any sort of warped ranking system that could be used to exclude people. The argument the students felt had the greatest strength was: to be made in the Image of God means human beings are able to relate to God and each other.

To be human is to be connected, to be dependent. The triune God, existing in community, created people for relationship. It is not a sign of the Fall that we need other people or we need God. In fact, it’s the Fall that says we can exist alone. It’s the Fall that says the normal mode of humanity is to be independent, self-sufficient , and totally self-made. But, if you’re pregnant, if you’re sick, if you’re a child, if you can’t earn money, if you have a disability, if you’re homeless, if you’ve experienced trauma, - you are not self-sufficient. And thus, the logic continues, you are dependent, and “less than”. It is the Fall, not the gospel, that says you’re less than human when you need others1. We all have innate worth - not because we are masters of creation or can solve equations and appreciate beauty. We have worth as God’s children - that’s a relationship word, a dependent word. Interdependency on God and others, that’s the full arc of redemption. That’s where the story is going2.

And that’s why I don’t think there are any small stories. This is why, now more than ever, we need to be reading stories like Little Women and The Penderwicks. Not because they are lighthearted tales about one little individual family that allow us to turn inward and ignore the chaos of the world outside our doors. But because they remind us of the joy and heartbreak and chaos that already teems within our own four walls. And in this, they highlight very clearly that no one exists alone. We are all embedded in relationships. I am because all of you are. Our actions affect others. We are not just a Rosalind or a Jane or a Batty or a Skye (or a Jo or an Amy, for that matter). We are Penderwicks. We are Marches. We exist in a neighbourhood, in a county, in a country. We are enmeshed and tangled up with other people, whether we like it or not.

And that’s not a bad thing.

It’s what makes us human. To need others, to have others need me - this is human. We need to remember that now, more than ever.

Just Beautiful Links

A round up of what we’re reading, listening to, and articles that spark me thinking about places where beauty and justice meet.

Last time I’ll share, but here are two links to recent Plough articles I’ve written. This one on interdependence and living in a Tiny House, and this one on scary fairytales. Friends- how fun! I’ve met quite a few people now due to the fairytales essay! It has been so fun to connect with readers! Thank you to everyone who messaged me!

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Just Beautiful to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.